College Accreditors: ‘Watchdogs That Don’t Bark’

Some years back, then US Secretary of Education Arne Duncan quipped that US college accreditors are “watchdogs that don’t bark.”

I chuckled at the refrain, which struck me intuitively as correct. I have since heard it repeated often by higher education critics on both the left and the right.

But, as much as Arne Duncan’s line made an impression, I never examined it critically, nor did I ever come across any work to fact-check it.

Is it true, in fact, that accreditors refrain from policing academic quality and student outcomes in colleges?

Just how asleep on the college quality ramparts are accreditors?

To answer this question, I set out a few months ago with my colleagues at Postsecondary Commission to examine the oversight activities of US college accreditors. We downloaded from various federal databases a trove of descriptive information on roughly 40,000 discrete acts of oversight taken by US accreditors toward colleges over the last decade. And then, in what I believe is the first quantitative analysis of its kind, we painstakingly analyzed each regulatory action to assess just how often (or not) college accreditors discipline US colleges for poor academic programming or inadequate student outcomes.

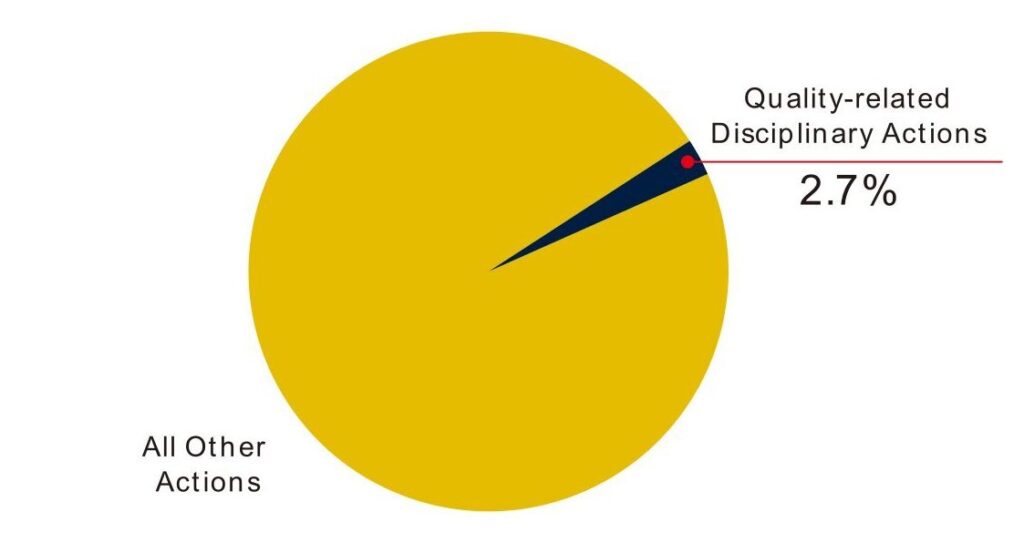

The answer, we found, is 2.7% of the time.

Meaning, a mere 2.7% of regulatory actions taken by accreditors towards colleges are ones that discipline colleges for low-grade student outcomes or inadequate academic designs. The other 97.3% of formal oversight activity by accreditors is supportive of academic designs and student outcomes in colleges, or it is focused on non-academic matters (mainly governance policies and finances).

Figure 1: Accreditor Actions, 2012-2022

Source: Postsecondary Commission analysis of the Database of Accredited Postsecondary Institutions and Programs, 2012-2022 (US Department of Education). Our full report, dataset and interactive charts are available at PostsecondaryCommission.org.

That accreditors do so little to sanction colleges for unacceptable student outcomes or dubious academic programming is inexplicable to me, considering the obvious problems in many colleges.

I am not smart enough to know exactly how often accreditors should sanction colleges for poor programming or student outcomes, but I do know from common sense that it needs to be more often than is currently the case.

College Accreditation 101

College accreditors might be the most important institutions in American society about which nobody has ever heard a peep. So, before saying more about our research into their behavior, some background is in order.

College accreditors arose in the early 20th century as voluntary membership associations. In this period, accreditors operated privately for the benefit of their member colleges, and they played no formal or consequential role in higher education policy or finance.

In the early 1950s, Congress vested legal authority in accreditors to vet and select colleges for higher education funding under the GI Bill. Accreditors’ role as gatekeepers of public aid for college expanded rapidly and significantly with the passage of the Higher Education Act (HEA) in 1965 and with the large increase in higher education funding that accompanied the HEA.

Since the passage of the HEA in 1965, American colleges can accept federal financial aid and qualify for most forms of state-level funding for higher education only if they are in good standing with a private accreditor recognized by the US Department of Education. In this regard, accreditors are immensely powerful. They control and direct the flow of vast public aid to US colleges.

In addition to positioning accreditors as gatekeepers of public spending on higher education, the HEA also tasks accreditors with reviewing college quality and with helping colleges improve. This legal charge and the choice of accreditors to dodge it so pervasively are the topic of this blog.

When monitoring and evaluating colleges, accreditors generally avoid setting and imposing objective standards for quality and competence. Instead, to monitor colleges, accreditors usually rely on self-study processes in which colleges evaluate their own success and on peer-review processes staffed by employees of other colleges.

The US Department of Education currently recognizes 60 accreditors. Forty-five of these accreditors grant institutional accreditation, a prized form of accreditation that allows postsecondary institutions to qualify for public aid. The other 15 accreditors are specialized programmatic accreditors that review specific educational programs and majors within colleges in a particular field of study (law, dentistry, architecture, etc.) and that generally do not influence the eligibility of colleges for public aid.

Importantly, accreditors are largely governed by delegates from the very colleges they oversee, and they depend financially on dues paid by their member colleges. They are also often staffed and led by former employees of the colleges they regulate. This arrangement creates obvious conflicts of interests and probably explains heavily why accreditors are so slow to discipline their members.

The Research Plot Thickens

The main insight of our research into accreditors – i.e. the finding that a mere 2.7% of actions taken by accreditors are ones that discipline or sanction a college for poor student outcomes and unacceptable academic programming – is backed up in our analysis with a string of fascinating sub-plots.

I’ll name four of them here, and you can find a dozen more in the report itself.

- “Rare and Random.” Low graduation rates, high loan default rates, and low median student earnings do not increase the likelihood that a college will experience a disciplinary action from an accreditor. Said differently, accreditor actions to regulate colleges for poor academic designs or sub-par student outcomes are not only rare, they are also random.

- “Picking on Small Barber and Beauty Schools.” In our analysis, approximately two-thirds of the (few) institutions that do incur a quality-related disciplinary action from an accreditor are 1-year certificate programs, many of them for-profit barber or beauty schools. Basically, when accreditors occasionally sanction a college because of poor outcomes or worrisome programming, they tend to pick on small, jobs-oriented certificate programs which, while they might warrant scrutiny, enroll very few students and play a peripheral role in higher education. By contrast, conventional 2-year and 4-year colleges — which enroll a large majority of US college students and which, in many cases, suffer egregiously from low graduation rates and poor jobs outcomes — are almost never policed by accreditors for bad outcomes and low-grade academic programming.

- “Money for Nothing.” Colleges in our sample receive approximately $112 billion annually in federal financial aid under Title IV of the Higher Education Act. Ninety percent of this funding goes to colleges that experience no disciplinary action related to academic quality or student outcomes. In short, accreditors exert minimal pressure on academic quality and student outcomes in colleges that absorb most public funding for higher education.

- “Regional Accreditors Gone Missing.” Seven large accreditors – often referred to as “regional” accreditors since they have traditionally dominated distinct areas of the country – oversee 95% of US college students and 68% of 2-year and 4-year colleges. These dominant accreditors are particularly unlikely to sanction colleges for objectionable student outcomes or academic programming. For example, only 1% of formal oversight activity by regional accreditors involves disciplining a college for sub-par student outcomes or low-grade academic offerings. Similarly, only 2% of the 13.9 million students overseen by regional accreditors attend colleges that incur disciplinary action from their regional accreditors for poor academic quality or low student outcomes.

The Punchline

US college accreditors – despite their powerful legal position as gatekeepers of public spending on US higher education and despite their assigned role by Congress and the US Department of Education as regulators of college quality – rarely take formal action towards colleges for breakdowns in academic programming or student outcomes.

Accreditors are, of course, not the only actors in higher education that skirt oversight of colleges. Our state and federal governments, for a variety of reasons, are no more inclined than accreditors to police college quality.

Still, accreditors loom large in the vacuum that is college quality control. They could wield enormous power, were they so inclined, to police college quality since their approval is a condition of the public funding on which almost all colleges depend.

Unfortunately, college accreditors are, as Arne Duncan labeled them, “watchdogs that don’t bark.” Or to be more exact and as our research shows, “watchdogs that bark 2.7% of the time.”

Looking Ahead

In the weeks ahead, I will blog again on US college accreditors. For the next go-round, I will take a close look at the extremes to which most accreditors go to deter the formation of new colleges. Accreditors’ hostility to new college formation is as regrettable, in my view, as is their disinterest (described here) in regulating the quality of programming and outcomes in existing colleges.

Thanks for reading along. More on accreditors soon.