10 Crucial Facts about Community College

Community colleges have been in the news a lot lately, mainly because they were contenders for a slot in Biden’s large spending bill.

Debates about community colleges — both this time around and in general — are often disconnected from important facts about them, in my opinion.

With that in mind, below I work up a Top 10 List of hard-nosed facts about community colleges. These are facts that I find essential to any understanding or discussion of community colleges.

For many years, even as I worked in and around K-12 schools and colleges, I knew little about community colleges. Like most Americans, I held a vague and generally pleasant view of community colleges as hard-working places that fought for students from all walks of life to help them get on their way to a sensible job or further BA studies.

Some years back — in part because we set out at Match Education to start a new college that serves students who in many cases would otherwise go to community colleges — I started to dig.

I have been learning ever since.

Fact 1 of 10: 29% of College Students Attend Community Colleges

Almost without exception, community colleges (sometimes called 2-year colleges) are public institutions, regulated and governed by state education agencies. They mostly grant 2-year degrees called Associate’s degrees.

Community colleges account for 1,303 of 3,982 US colleges and for 29% of 19.6 million college students.

Ninety-six percent of community college students attend 853 public community colleges. The remaining 4% of community college students attend 450 small, private community colleges.

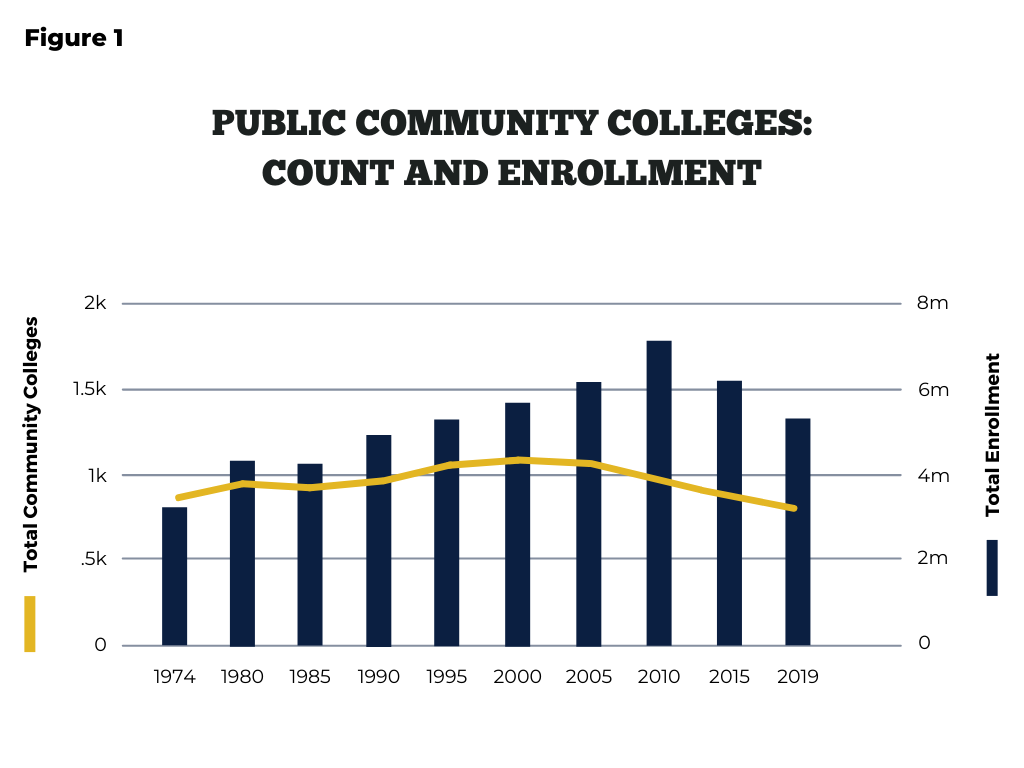

Enrollment in community colleges expanded handily over the last 50 years, even as the number of these colleges remained largely unchanged.

Fact 2 of 10: Most Community College Students Commute and Work

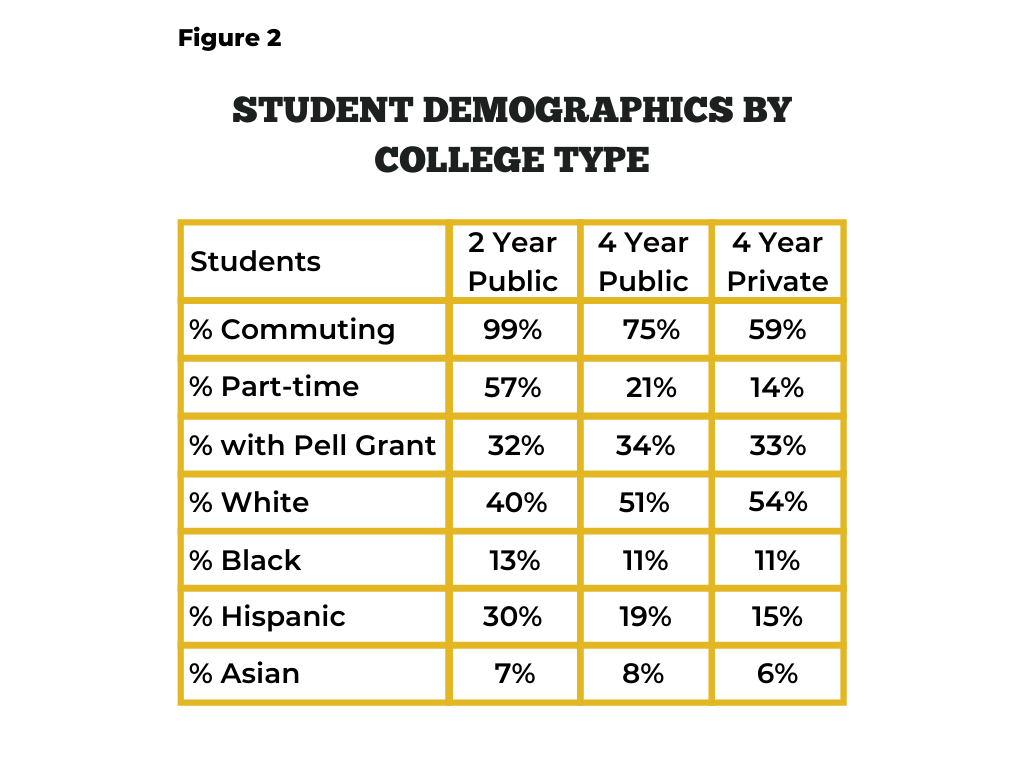

Community college students deviate from their 4-year college counterparts mainly in that they are far more likely to commute to college and to be part-time students (often because they hold jobs).

Fact 3 of 10: 28% of Community College Students Graduate

Graduation rates in US community colleges are shockingly low.

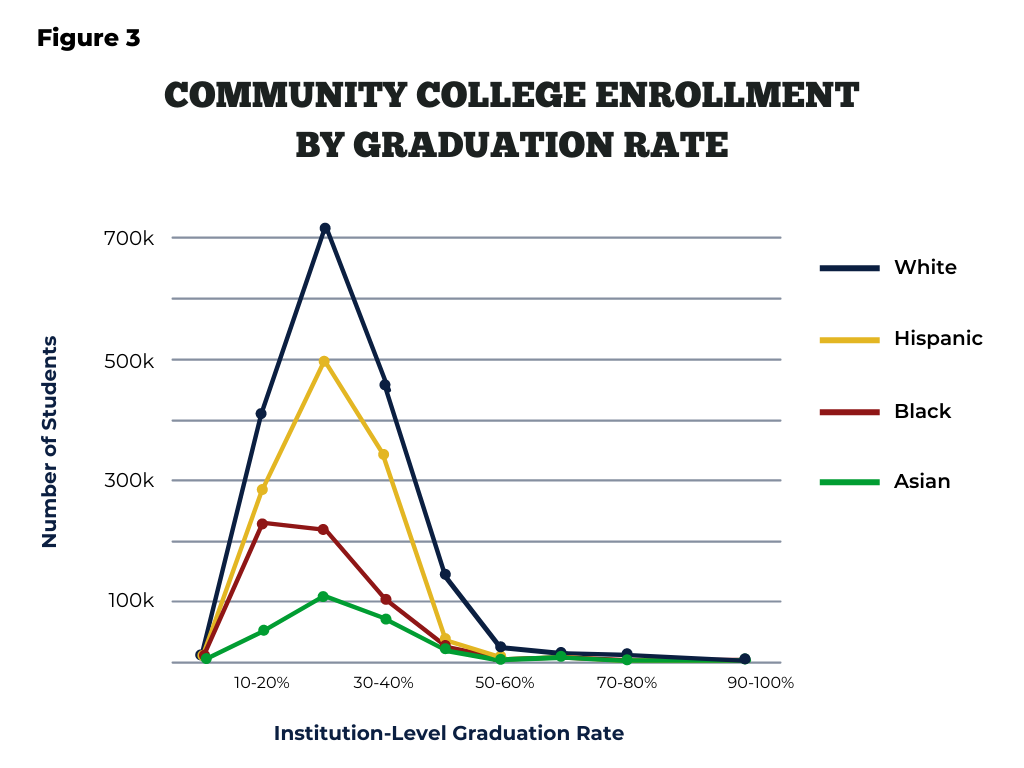

A mere 28% of first-time and full-time students in community colleges earn an Associate’s degree within three years.

This low average graduation rate deteriorates starkly among most non-white sub-groups. For example, only 18% of Black first-time and full-time community college students earn a degree within three years.

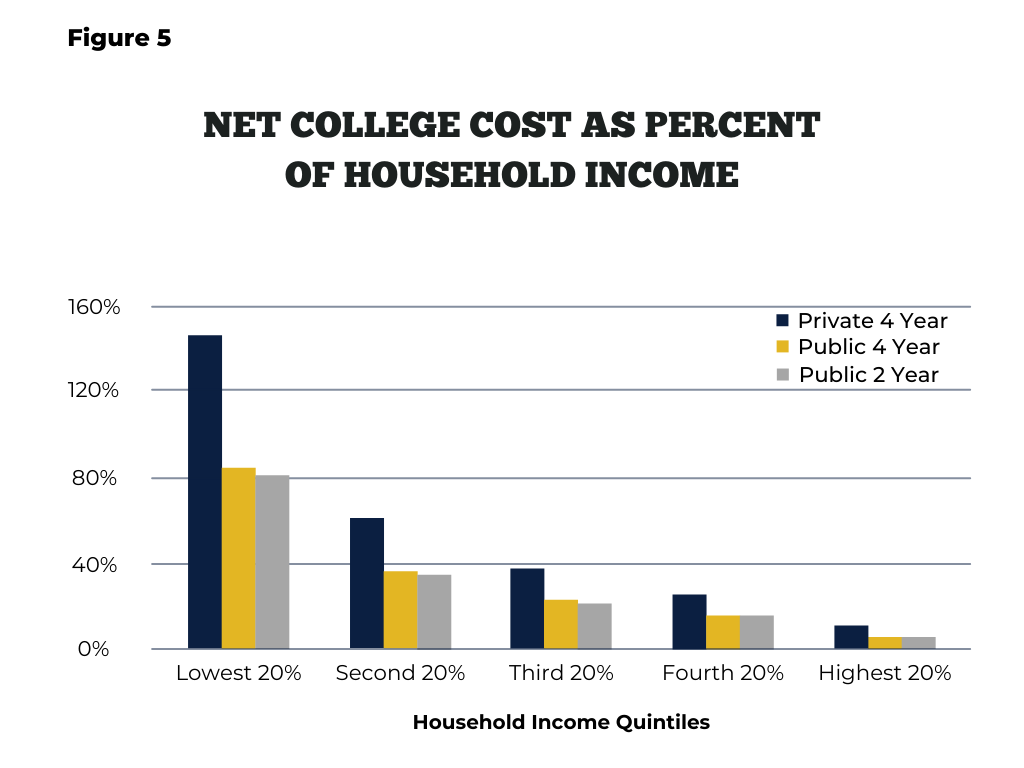

Fact 4 of 10: Community Colleges are Expensive for Lower Income Families

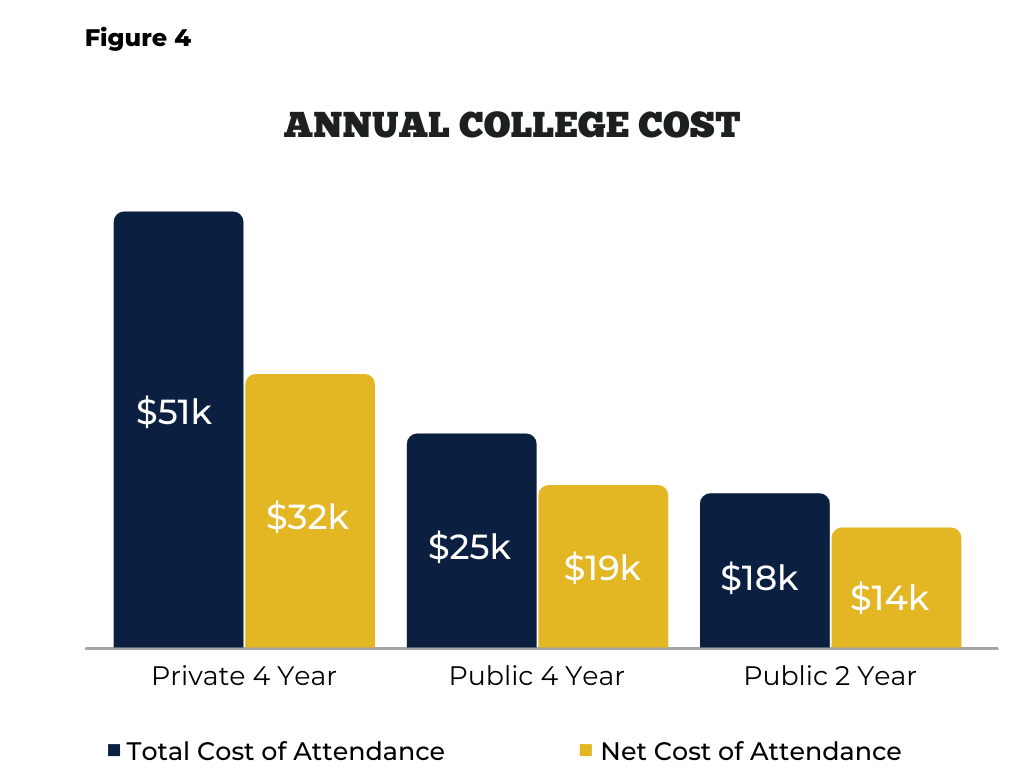

The total cost of attending a community college — that is, the sum of advertised tuition, room and board, and various college-related fees — is currently $18,830 per year.

More importantly, the net total cost of attending community college — or the actual cash cost of attendance to a student, after government grant aid (notably Pell grants) and college-issued tuition discounts — is $14,370 annually.

Though the most affordable college option in the US, community colleges are financially onerous for many low-income students.

For students in the lowest 20% of the US income distribution, the net total cost of attending community college equates to 81% of their annual household income.

Fact 5 of 10: The Price of Community College has Outpaced Inflation for Decades

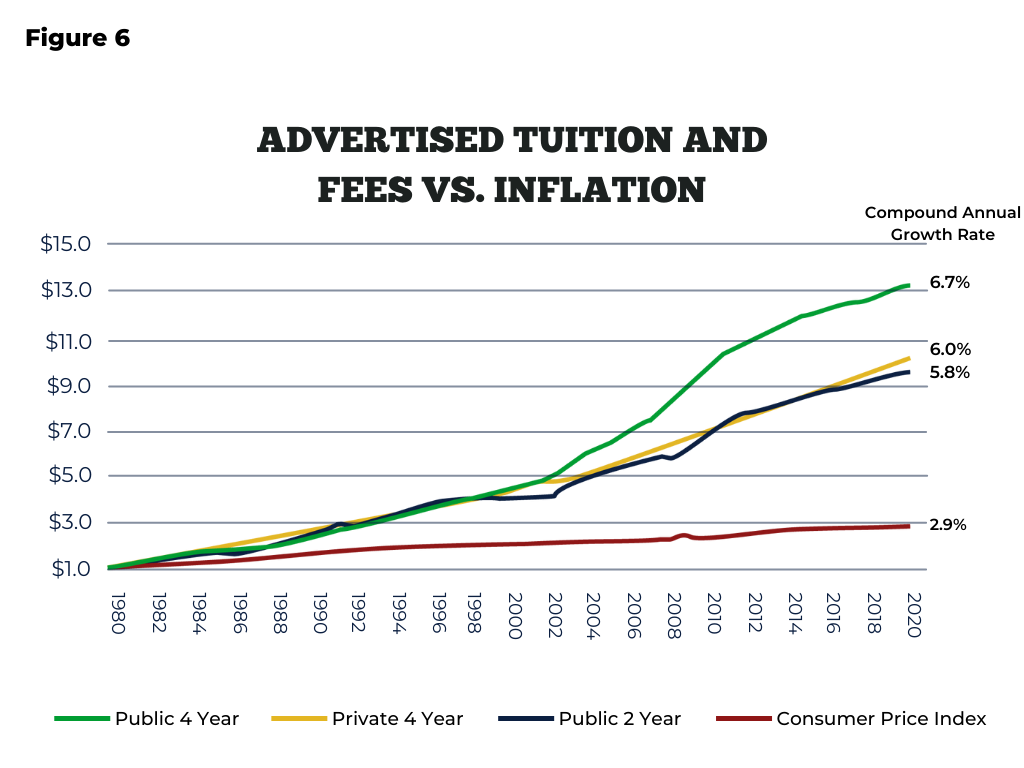

The cost of community college has risen ahead of inflation significantly and without interruption for decades. The chart below compares advertised tuition and fees at various types of US colleges with inflation over the last 40 years.

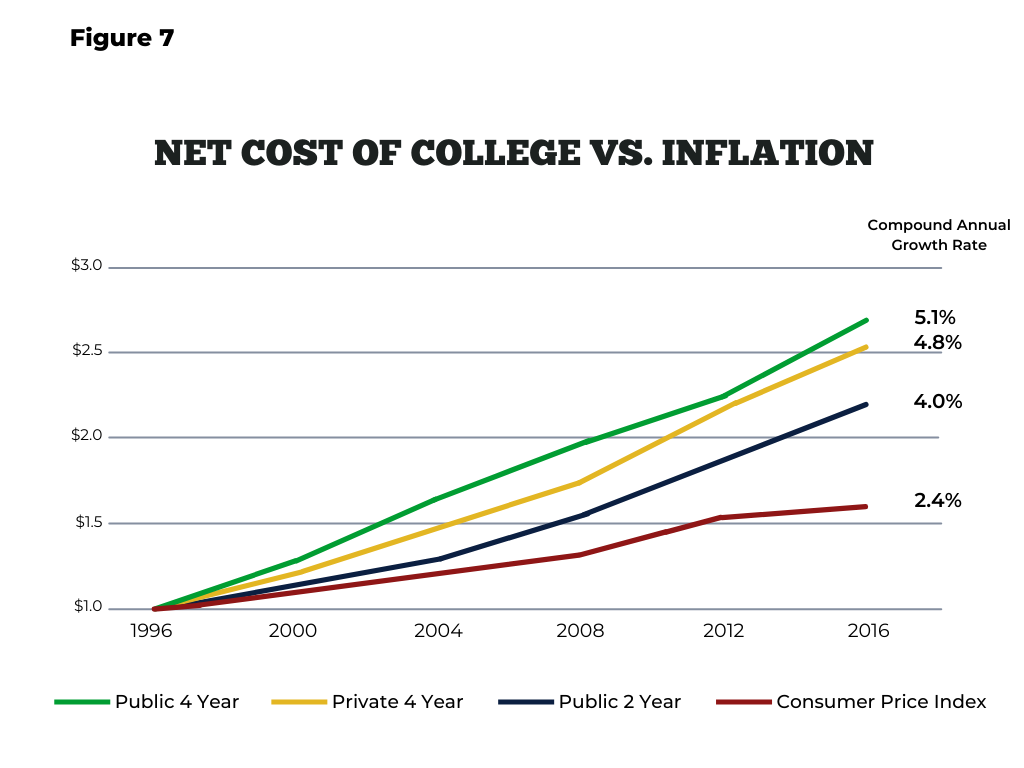

The net cost of community college has also expanded persistently ahead of inflation for many years. This is true even for low-income students who are most likely to receive Pell grants and college-issued financial aid.

Fact 6 of 10: Job Outcomes are Erratic for Graduates and Dismal for Dropouts

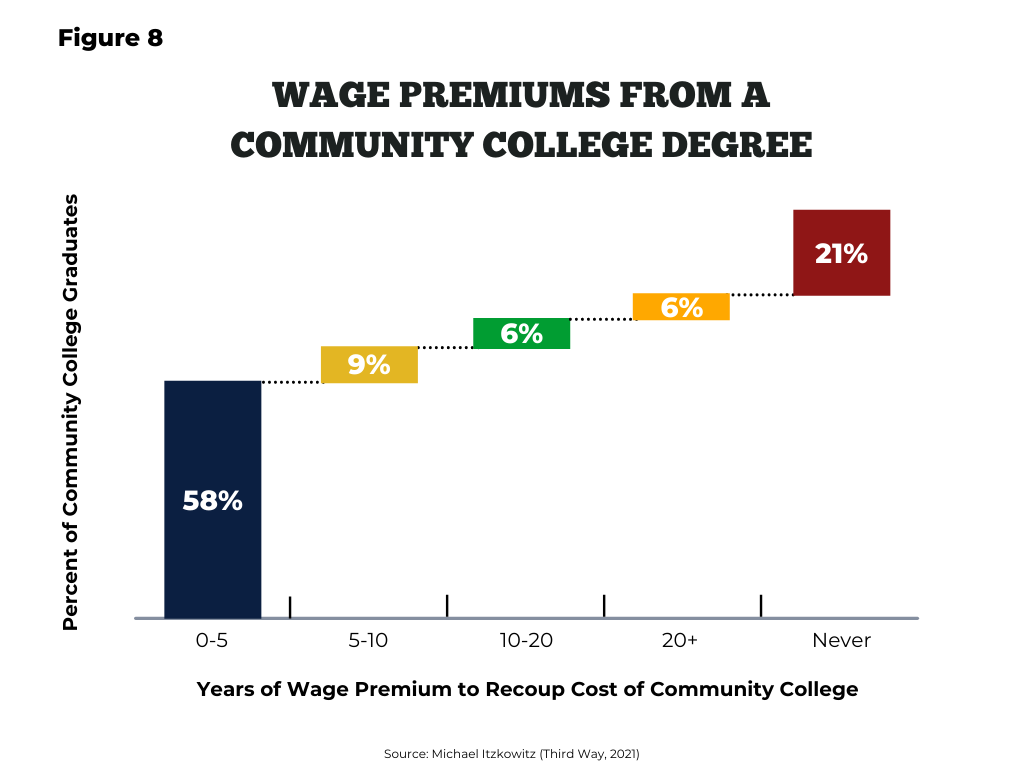

The primary reason that students attend community college is the prospect of a better and higher-paying job after graduation.

Unfortunately, for the sub-set community college students (28%) who complete their degree, uncertain job prospects await.

When researchers examine the wage premium that follows from completing community college — that is, when they compare the earnings of community college graduates to the earnings of similar high school graduates — they find that approximately one-third of community colleges graduates will never make added wages equal to the cost of their degree or will need to work for decades to do so.

Wage premiums from a community college degree vary enormously by subject. Notably, community college degrees in nursing and in STEM fields typically pay off well, whereas degrees in the liberal arts often fail to produce earnings improvement for graduates.

The labor market and financial consequences of going to college are, of course, most problematic for students who never finish and who, in many cases, leave college with debt and no degree.

For these non-completers — who constitute 78% of community college students — community college is often devastating.

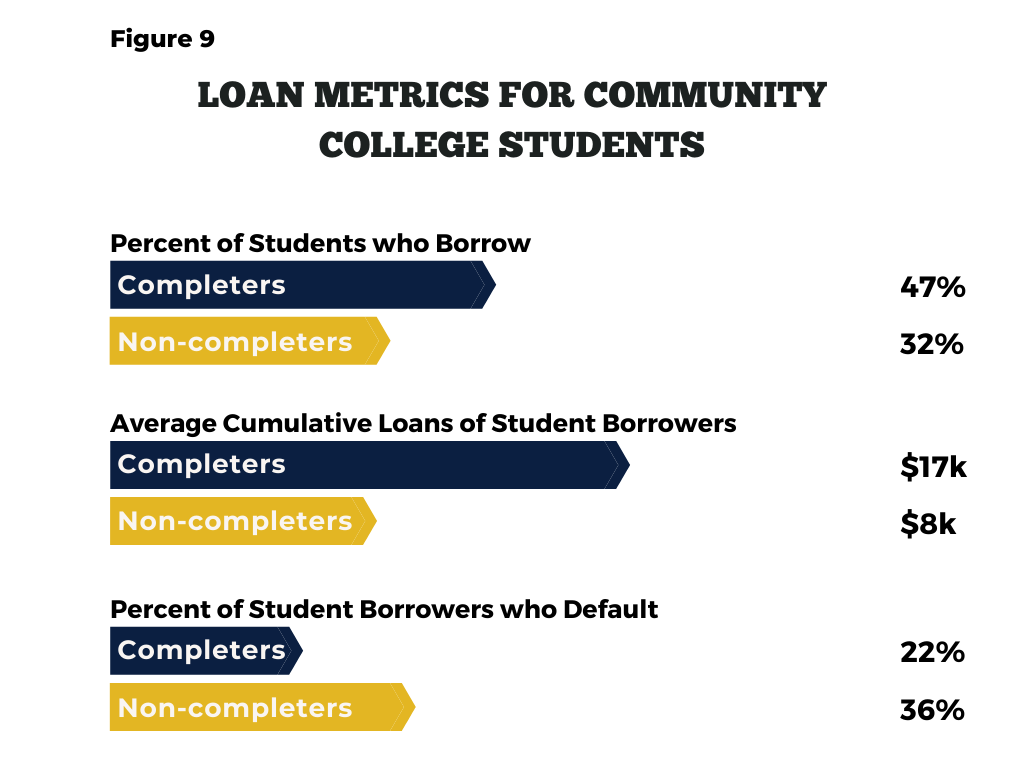

Thirty-two percent of community college dropouts borrow during their incomplete college experience. These borrowers leave college with an average of $8,131 debt, and they default on their college loans 36% of the time, a rate substantially higher than that of their peers who earn a degree.

Fact 7 of 10: Community Colleges Face Organizational Barriers to Innovation

- Mired in Fixed Costs. Community colleges are typically bogged down in real estate and in entrenched salary obligations to staff who are variously tenured, unionized, and protected by civil service regulations. Turning over staff, selling real estate, and reconfiguring resources – all of which need be options for an innovative college seeking a faster, better, and cheaper model – are not feasible in most incumbent community colleges.

- Low on Cash and Protective of Existing Revenue. Most community colleges have few cash reserves and live payroll-to-payroll on their tuition collections and public funding. As a result, most existing colleges are barred from investing in the one-time losses that invariably accompany new product design and fearful of novel, improved designs that might cannibalize their existing offerings and crucial short-term revenue.

Fact 8 of 10: Starting a New Community College is Almost Impossible

With vanishingly rare exceptions, new community colleges do not arise.

At Postsecondary Commission, we can identify only 8 new community colleges that have been started over the last 20 years. These community college startups educate a miniscule 0.2% of community college students.

To start a new college requires clearing two hurdles. The first step is to convince a state education commission to approve a new college. With some time and effort, this can be done. The second step is to persuade a private accreditor to sign off on a new college. Without accreditation, a college cannot accept payments from students who rely on Pell Grants, federal loans, or public financial aid of other kinds.

This second step is essentially insurmountable because accreditors maintain an impossibly onerous, time consuming, and expensive process for greenlighting a new college.

One byproduct of accreditor’s hostility towards the formation of new community colleges (and colleges of any kind) is that higher education funding remains with incumbent colleges, free of competition from new arrivals.

Fact 9 of 10: Community Colleges Face Almost No Accountability

Community colleges almost never close for reasons related to academic quality or student outcomes. They are given a pass on quality from the public agencies that fund them and from the private accreditors that allegedly monitor them.

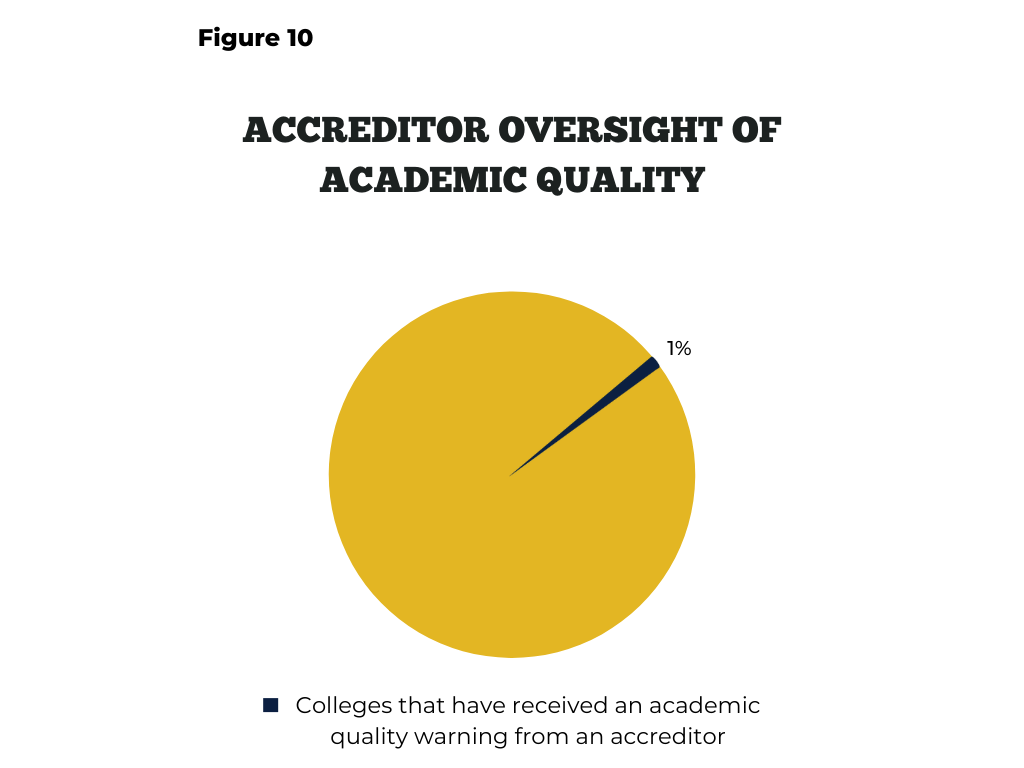

At Postsecondary Commission, we recently examined the administrative records of accreditors for the past several decades. We found that only 1% of US colleges (of any kind) have received a warning or a pointed inquiry from an accreditor about academic quality.

Like accreditors, state and federal governments also decline to police academic quality and outcomes in community colleges.

Confronting colleges – even struggling ones — is invariably bad politics. All colleges, no matter their performance, have highly motivated supporters (faculty, alumni, community members), and higher education as a sector is well-organized politically. Most politicians – state or federal — know better than to sanction a college.

Fact 10 of 10: 79% of Community College Revenues are Subsidized

Community colleges are not only protected from new entrants and shielded from accountability. They are also heavily subsidized by public funding.

In particular, 79% of community college revenue originates in public subsidies. These subsidies take the form of operating aid to colleges (mainly from state appropriations) and tuition aid to students (mainly via Pell grants).

Conclusion

So, those are some facts — important ones in my view — about community colleges. I hope the long read was worth it.

Endnotes

- Figure 1: Public Community Colleges: Count and Enrollment relies on data from the NCES Integrated Postsecondary Education Data System (IPEDS). This figure includes only public community colleges.

- Figure 2: Student Demographics by College Type includes data on both public and private 2-year colleges. Data on commuters is from NCES and from the National Postsecondary Student Aid Study (2016). Data on part-time students, on Pell grant students, and on student demographics are from College Scorecard data releases in 2018-19.

- Figure 3: Community College Enrollment by Graduation Rate includes public 2-year colleges and excludes a small number of private 2-year colleges. It is drawn from IPEDS data files. The chart groups community colleges into deciles according to their 3-year graduation rate, and it tallies enrollment in each of these deciles.

- In Figure 4: Annual College Cost, cost of attendance data on public 4-year colleges is for in-state students. Data is from CollegeBoard: Trends in College Pricing 2020.

- Figure 5: Net College Cost as a Percent of Household Income is drawn from CollegeBoard: Trends in College Pricing 2020.

- Figure 6: Advertised Tuition and Fees vs. Inflation relies on data from CollegeBoard: Trends in College Pricing 2020.

- Figure 7: Net Cost of College vs Inflation is drawn from NCES NPSAS data.

- Figure 8: Wage Premiums from a Community College Degree is excerpted from Michael Itzkowitz’s article, “Which College Programs Give Students the Best Bang for Their Buck?” (Third Way, August 2021).

- Figure 9: Loan Metrics for Community College Students

-Data in Percent of Students who Borrow is primarily from Beginning Postsecondary Survey (2012-17). Data includes private and federal loans through 2017 and is limited to public 2-year colleges.

-Data in Average Cumulative Loans of Student Borrowers includes Direct Federal Loans and excludes Parent PLUS and private borrowing. Data on completers is from NPSAS 2016, and data for non-completers is from BPS 2012-2017. The chart is limited to public 2-year colleges.

-Data on Percent of Student Borrowers who Default is compiled from BPS 2004-09. Default rates are from cohorts that precede the rise of income-driven repayment policy, which lowered default rates on all types of loans. Data includes only public 2-year colleges.

- Data in Figure 10: Accreditors Oversight of Academic Quality and data throughout on the administrative behavior of U.S. accreditors (including the rate at which they approve new colleges and the likelihood that they will review a college for academic quality) are from proprietary Postsecondary Commission analysis of NACIQI data on accreditor administrative actions. NACIQI data includes for-profit colleges.

- Figure 11: Subsidies for Community College is derived from Integrated Postsecondary Education Data System (IPEDS) data.