Concerning Commonwealth Colleges

I live in Massachusetts, went to graduate school here, and teach entrepreneurship part-time at Harvard Business School. So, with my backyard in mind, I take a close look in this blog at the college scene in the Commonwealth.

What I lay out here might surprise you.

- Pockets of Abysmal Graduation Rates. Graduation rates are shockingly low in many Massachusetts colleges and in certain corners of the college sector here. For example, only 20% of students and 13% of Black students graduate within 3 years of starting in a community college in our state.

- Price-to-Earnings Noise. The price of a 4-year degree in Massachusetts does not predict the salaries of typical graduates two years after graduation. What students pay to attend a Massachusetts college tells them almost nothing about what they will make after graduation.

- Money-Losing Degrees Abound. While many degree programs are sound investments for students interested in improving their short-term earnings potential, 26% of degree programs in Massachusetts are money losers for most students. Typical graduates from these degree programs often earn less, a few years after completing college, than do similar working adults with only a high school degree.

- Majors Matter. The choice of a major – unlike the price of a degree – heavily predicts salaries after graduation. Unsurprisingly, STEM-related majors (in almost any college setting) pay back the fastest.

This blog is a redaction of a research report that I published a few weeks ago with Yazmin Guzman (a colleague at Postsecondary Commission) and Michael Itzkowitz (a Senior Fellow at Third Way, a DC think-tank). You can find the full report here.

The Basics

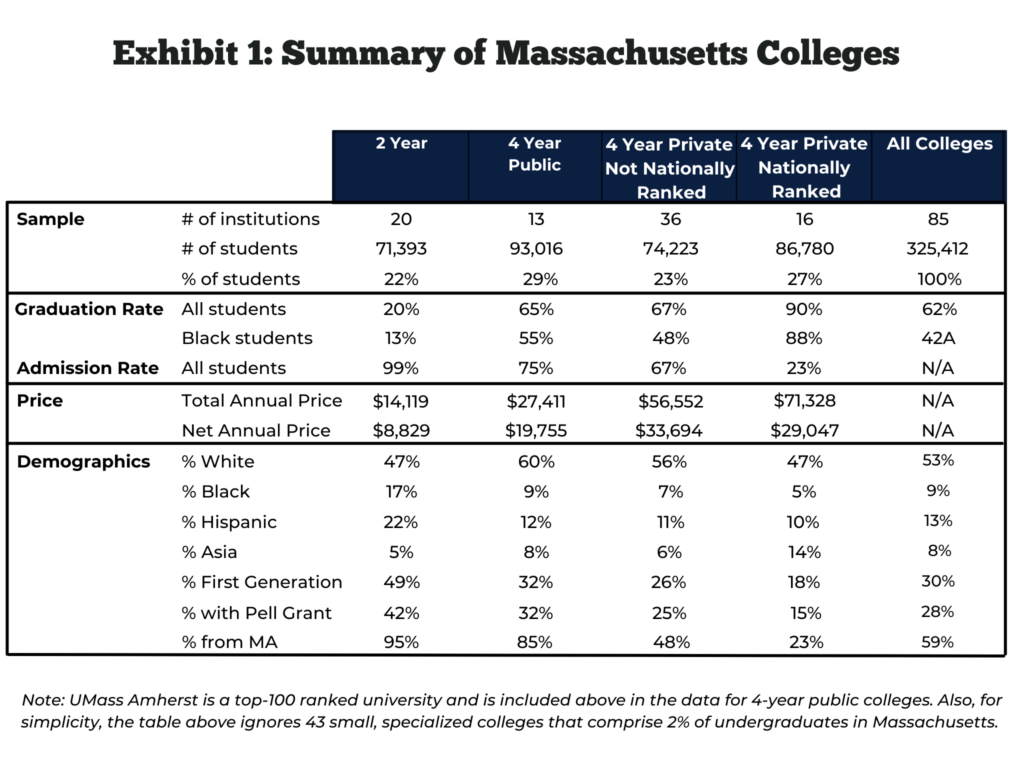

The table below characterizes the 85 main colleges in Massachusetts. These colleges enroll 325K undergraduates and account for 98% of the Commonwealth’s college population. Their student bodies range in size from 350 to 24,000 students.

Spend a minute on the table below. I’ll return to it throughout this blog.

Put Aside the Top-100 Types

Our state is home to an unusual concentration of nationally ranked private colleges that are named regularly by US News & World Report and other rankings-crazed publications as top-100 universities. We have 16 of these nationally noted colleges in Massachusetts. Think MIT, Williams, Boston College, Tufts, Harvard, and so on.

In this analysis, I treat separately and generally ignore these colleges. While they comprise about a quarter of college students in the Commonwealth, they enroll few in-state students and matter little to typical college-going students and families in the Commonwealth.

As I move on from these colleges, some parting facts about them:

- Fewer Students from In-State. 23% of students in our state’s 16 nationally ranked colleges are from in-state high schools or resided in Massachusetts before enrolling. By contrast, 95% of students in our community colleges and 85% of students in our public 4-year colleges are locals.

- Lower Admission Rates. These nationally ranked colleges are highly selective, sometimes in the extreme. Harvard admits less than 5% of its applicants.

- Fewer Low-income and Fewer First-generation Students. Compared to other colleges in Massachusetts, especially public ones, nationally ranked private colleges enroll far fewer students who are Pell grant recipients and far fewer students who are the first in their family to attend college. For example, 49% of students in our 2-year colleges are first-generation college-goers, compared to 18% of students in nationally ranked colleges.

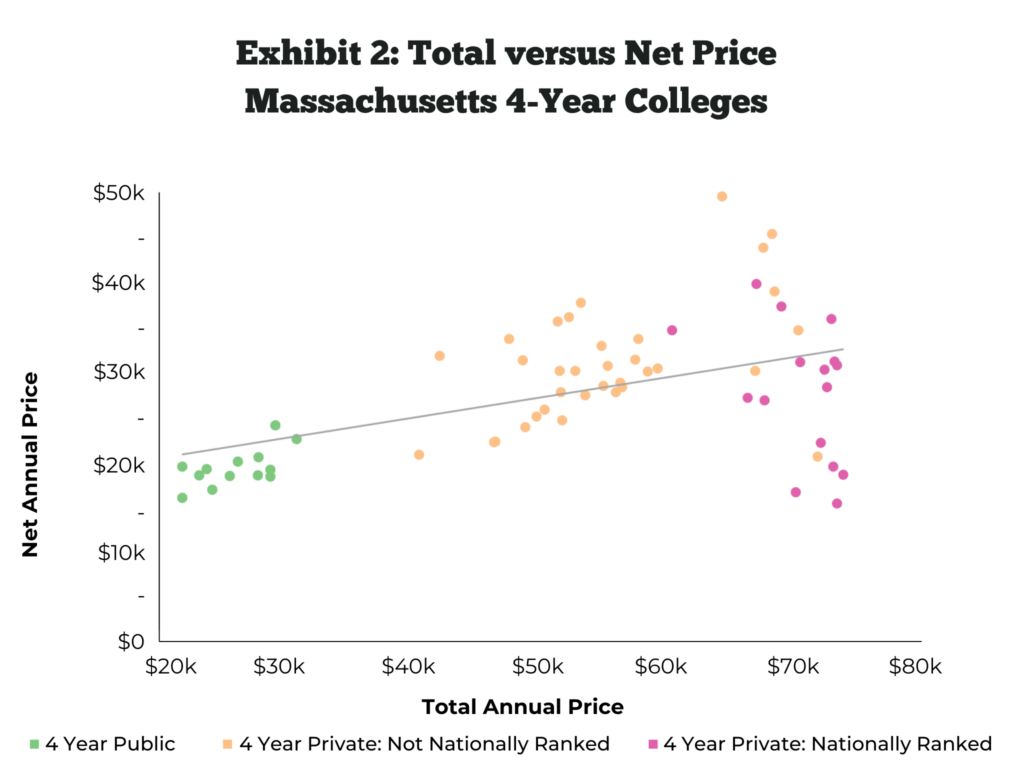

- Higher Levels of Financial Aid. Nationally ranked colleges are surprisingly affordable for low-income students because they issue high levels of financial aid, usually enabled by endowment returns. The chart below illustrates this point by plotting the total price (i.e. the full price of tuition, room, board and fees) and average net price (i.e. the total price of a college minus the average public aid and college-issued discounts granted to students) of 4-year colleges in the Commonwealth.

Graduation Rate Elephants in the Room

College conversations in Massachusetts tend towards the self-congratulatory, I believe. They often linger, as far as I can tell, in a glowy assumption that we do better than other states.

But on the all-important measure of whether our colleges are designed for degree completion, our colleges are average or worse.

- 20% Graduation Rate in 2-Year Colleges. The graduation rate in US public community colleges is 28%. In Massachusetts, the situation is even more dire. Our community colleges have a 20% graduation rate overall, and Black students in our state’s community colleges graduate 13% of the time. I am not smart enough to know what the optimal graduation rate should be in our community college system which, to its enormous credit, admits all applicants. But it should not be this low.

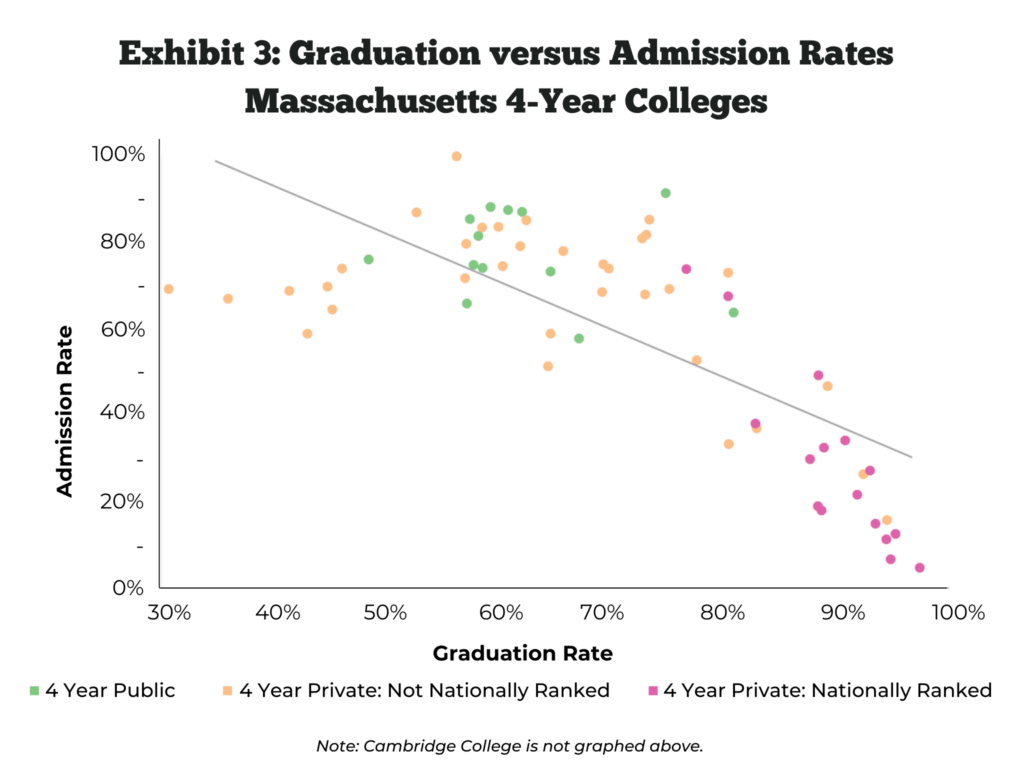

The graduation rate situation in our 4-year colleges is also no cause for celebration. Below is a chart that plots the graduation and admission rates of our 4-year colleges.

To me, three points are worth making from the chart above.

- Woefully Average Graduation Rates in our 4-Year College System. Graduation rates in our 4-year colleges – once the completion results of super-selective colleges are removed from the calculation – are eminently average. National graduation rates in 4-year public and 4-year private (nonprofit) colleges are 61% and 67%, respectively. In Massachusetts, similarly, 67% of students in private 4-year colleges (that are not nationally ranked) and 65% of students in 4-year public colleges graduate.

- The Easiest Way to Graduate a Lot of Students is to Reject a Lot of Applicants. Outstanding graduation rates, where they exist in Massachusetts, correlate strongly with extremely low admission rates. Notably, almost all colleges in Massachusetts that graduate 90% or more of their entrants admit fewer than 20% of their applicants.

- Some Non-Selective 4-Year Colleges are Unsung Graduation Rate Heroes. Modestly selective and non-selective 4-year colleges (i.e. colleges with admission rates greater than 40%) vary widely in their graduation rates. Some of these 4-year colleges, to their credit, produce high graduation rates even as they admit students generously.

Price-to-Earnings Noise

Most college students view college as a ticket to a well-paying job. They choose among colleges and pick majors based, more than anything else, on their need for a good salary and strong career prospects after graduation.

On this crucial topic, the US Department of Education recently released a trove of new data on the short-term earnings of graduates from specific degree programs in Massachusetts colleges.

The new data set covers 52,448 graduates who finished college in 2014-15 or 2015-16. These students graduated from 1,071 degree programs, all administered in one of the 85 colleges profiled above.

The chart below plots these 1,071 degree programs by their average net price and by the earnings of a typical graduate two years after completing college.

A college’s net price, recall, is the average out-of-pocket cost to a student to attend college. It is calculated as the full, advertised cost of college (i.e. tuition, fees, room, and board) minus the average amount of support (in the form of government-issued tuition grants, mainly Pell grants, and college-issued financial aid) given to students.

Two immediate observations stand out from the diagram above.

- Weak Relationship Between Degree Price and Short-term Earnings. In Massachusetts, the price of a degree does not predict in any reliable way how much a typical graduate from that degree will earn two years after completing it. Pick a price point on the x-axis above and read upwards. You will notice enormous variation in the short-term earnings of typical graduates from degree programs that cost the same.

- High Degree-level Variation in Price-to-Earnings. Individual degree programs vary enormously in their prices, in the earnings prospects they generate for their graduates, and in the relationship of those two degree traits. Some degrees cost very little in relation to the short-term earnings experienced by typical graduates. For other degrees, the opposite is true.

26% of Degrees are Short-term Money Losers

A thoughtful way to evaluate a degree program is to quantify the wage premium it generates for its graduates (i.e. to estimate how much added salary a typical graduate earns because of having the degree) and to compare that wage premium to the average net price of the degree.

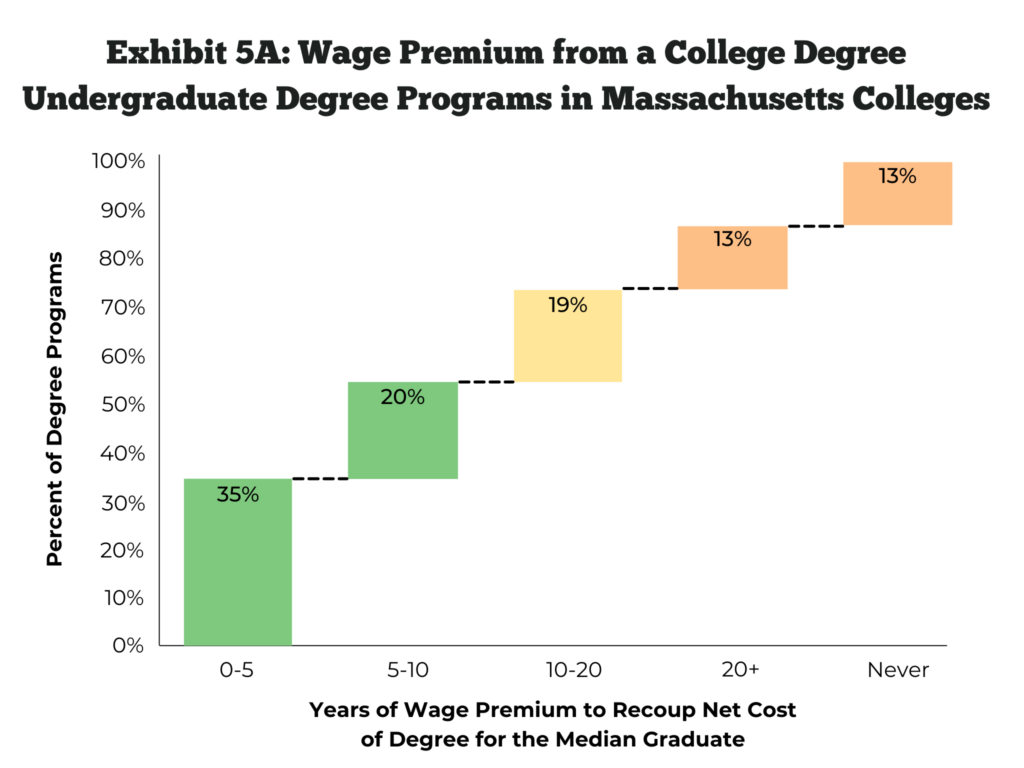

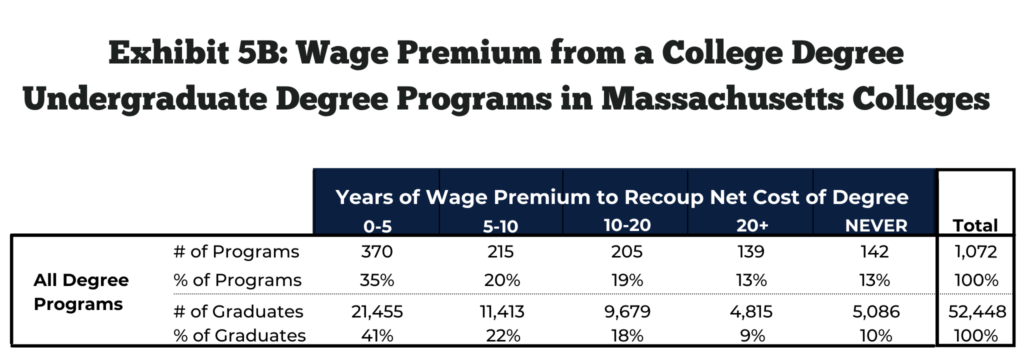

My colleagues and I did this analysis for degree programs in Massachusetts, and the results are below. The chart groups 1,071 degree programs in Massachusetts by how long a typical graduate needs to work in order to pay back the average net cost of a degree via the wage premium generated by the degree. The table below it summarizes these findings.

At least two points surface in the analysis above.

- 55% of Degree Programs Pay Back in Less than 10 Years. A majority of degree programs in Massachusetts generate substantial short-term wage premiums for typical graduates and allow them to recoup the cost of college in less than 10 years. Specifically, in 55% of degree programs in Massachusetts colleges, typical graduates experience wage premiums two years after completing college (i.e., wages in excess of those they would have earned if they had only a high school degree) that allow them to recoup the cost of their degrees, via those added wages, in less than 10 years.

- 26% of Degree Programs Yield No Wage Increase or Take 20+ Years to Pay Back. By contrast – and this should be a cause for concern, if not alarm – in 26% of degree programs in Massachusetts colleges, typical graduates experience either no wage premium two years after completing college (i.e. they earn less than they would have if they had only graduated from high school) or a modest wage premium that requires them to work for 20+ years to recoup the cost of college from added wages. These programs offer little or no short-term financial return on the cost of college.

The main observation here – again – is that degrees vary enormously in the short-term “bang for the buck” they produce for their typical graduate. A majority are good deals, but a substantial minority are money losers.

Majors Matter Massively

If students cannot predict how much they will make after college by the price they pay to go to college and if degrees are all over the map in how likely they are to generate short-term wage increases, then what is an ROI-driven student to do?

The answer, in part, is to focus on choosing an economically viable major. Picking a field of study is key to locking in a good salary after graduation.

In the chart below, I organize 884 bachelor degree programs in Massachusetts into broad fields of study and, for each field, plot the percent of degrees that allow typical graduates to pay back the cost of college, via its wage premium, in less than 10 years.

Degree programs in some fields of study are very likely to generate high short-term financial returns. For other fields of study, the opposite is true.

- High-Paying Outliers. For example, in our Massachusetts sample, Bachelor’s degree programs in engineering and computer science always allow typical graduates to pay back the average cost of their degrees, via added wages, in less than 10 years. Degree programs in the fields of mathematics, economics, and statistics have equally exceptional short-term financial returns, as do degree programs in business.

- Low-Paying Outliers. By contrast, degree programs in the arts (music, film, drama, etc.) have very low short-term financial returns. Notably, in our sample, 72% of arts-related Bachelor’s degrees generated no wage premium for a typical graduate or required 20+ years of work by the graduate to recover the average cost of the degree.

The bad news from all of this earnings data is, of course, that prices are unreliable signals of salary outcomes and that degrees offer a bewildering range of economic returns.

The good news, perhaps, is that economically minded students and families – if they shop carefully and dig deep on available data on prices and outcomes – can find colleges and degree programs that are reasonably priced and likely to generate an appealing financial return.

Conclusion

The material in this blog should raise wide-ranging questions about the college sector in Massachusetts. I hope it stirs debate.

To me, one immediate conclusion from the analysis is that our colleges — and the public agencies and accreditors that oversee them — should ramp up efforts to collect, organize and share data on college earnings outcomes with students and families.

Students have an obvious and urgent interest in fuller information about the financial outcomes of colleges and degrees within them. All stakeholders – regulators, politicians, accreditors, and colleges themselves – should rally to this cause. On that suggestion, I would think, nobody can disagree.

The broader and deeper policy take-away from this analysis, in my view, is the urgent need for new colleges and true innovation in the higher education sector in Massachusetts.

I have argued elsewhere that most colleges (including the ones in Massachusetts) cannot change and improve in meaningful, lasting ways. Most of them are mired in fixed costs, wedded to short-term revenue models, and hamstrung by bureaucratic governance. They are structurally prohibited from real change. Even if held accountable and funded in new and more thoughtful ways, most colleges will keep doing what they are doing.

The way to a better college sector – one that costs less and does more to improve the life and work prospects of its graduates – is to create a strictly regulated path into the college sector for nonprofit startup colleges. These startup colleges would pursue innovative designs (as only startups can) and would bring to the Commonwealth’s college sector fresh ideas, new designs, and competition.

Creating a tightly monitored access point into higher education for nonprofit college startups is the primary goal of the Postsecondary Commission, and I write about it often. This goal makes as much sense in Massachusetts as it does across the country.

I’ll leave it there for now. Thanks for reading along. Happy New Year, one and all.

-Stig