College Accreditors: ‘New Colleges Need Not Apply’

A few weeks ago, I blogged about the reluctance of US college accreditors to discipline their member colleges for poor student outcomes or low-grade academic programming. Accreditors, according to our research, devote a mere 3% of their formal oversight activities to policing worrisome student outcomes or academic programing. That accreditors skirt regulating college quality is inexplicable, in my view, given the obvious breakdown in student outcomes on many campuses. College accreditors control the flow of public aid to colleges, and they could exert enormous pressure, were they so inclined, on lax colleges.

In this blog, I take up a second (and, to me, also troubling) accreditor dynamic: the rate at which college accreditors approve new colleges and, when they do, the types of colleges that emerge.

To study this issue, my Postsecondary Commission colleagues and I sifted through federal databases to locate and analyze every documented episode of startup college accreditation stretching back to the dawn of American colleges. We looked in particular at current US colleges to pin down when they were accredited and by whom.

Our analysis found repeatedly that new college accrediting is vanishingly rare and, when it does occur, results in colleges that reach very few students.

The slow pace of new college formation in US higher education, in my opinion, poses a needless deterrent to improvement in the sector. It robs the sector, as I will discuss at the end of this blog, of the unique and powerful contribution that innovative, well-regulated college startups could make to the cause of improving US colleges.

Below are four highlights from our study, which you can read in full here.

By the way, before I dive in, recall that college accreditors might be the most important institutions in American society about which nobody has heard a peep. If you are curious about the backstory on US college accreditors, take a look at my earlier blog on accreditor oversight of college quality. In that blog, I summarize what accreditors do, who they are, and – most importantly – how they acquired their powerful legal standing as the gatekeepers of public aid to colleges.

Finding 1: Most Students Go to Old Colleges

US undergraduates overwhelmingly attend old colleges. 98% of current US undergraduates attend colleges that are more 20 years old, and 92% of them study at colleges that are more than 40 years old.

College Enrollment by Age of College (1)

College Enrollment by Age of College (2)

Finding 2: Most 2YR and 4YR Colleges are Old

Relatedly, 2YR and 4YR colleges – which account for ~90% of US undergraduates – are an old lot. For example, only 9% of 2YR colleges and 7% of 4YR colleges are less than 20 years old.

College Count by Age of College

Finding 3: Recently Approved Colleges are Mostly Small, Specialized and For-profit 1YR Colleges

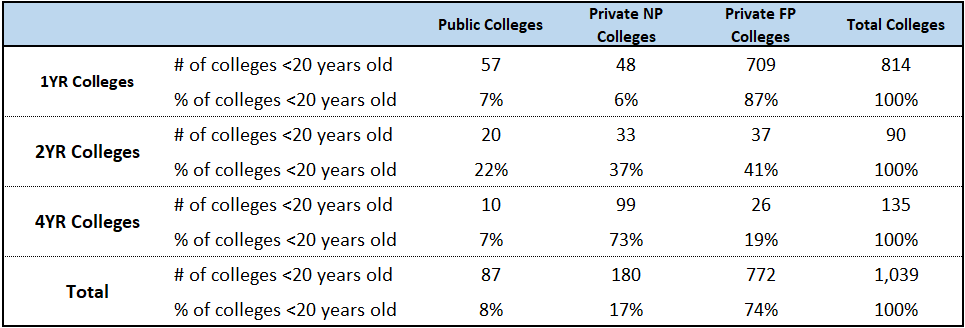

Of the 4,968 current US colleges that we examined, 1,039 (21%) were accredited in the past 20 years. These recently formed colleges – while numerous – are immaterial and peripheral in practice.

First of all, their reach is miniscule. As mentioned, they educate in combination 2% of US college students. They include almost no 2YR and 4YR colleges with broad student reach.

They are also highly specialized. 814 (78%) of the 1,039 current colleges that arose in the last two decades are 1YR institutions which usually offer a narrow range of jobs-oriented certificates in specific areas of employment (e.g., cosmetology, industrial trades, and health services).

Lastly, the 1,039 current colleges that arose in the last 20 years – in addition to being small, specialized 1YR institutions – are mostly for-profit colleges. 772 (74%) of them, to be exact, are for-profit institutions.

Colleges Accredited in the Last 20 Years

Finding 4: Accreditors Appear Disinterested in New College Formation

As a group, accreditors are slow as molasses in approving new colleges of any consequence to students.

This feet-dragging is most apparent among the seven regional accreditors that have a stranglehold on accrediting the 2YR and 4YR colleges that enroll most US undergraduates. Regional accreditors greenlighted only 84 (8%) of the 1,039 current colleges that won accreditation in the last 20 years. By contrast, national accreditors approved 955 of existing colleges that are less than two decades old.

Colleges Accredited in the Last 20 Years by Accreditor

The Need for New Colleges and Related Accreditation Reform

The rarity of new college formation in US higher education and the hostility of existing accreditors to startup colleges with meaningful student reach are a needless limitation on progress and innovation for the sector, I think.

Most observers of US higher education call on colleges to improve. They agree generally that too many colleges now cost too much, graduate too few, and result too often in shaky career outcomes. But oddly, they usually point only to incumbent colleges as agents and sources of change. That boggles my mind. Existing colleges, as I have written elsewhere, are highly resistant to wholesale change. They face deep-seated organizational impediments to innovation, and they are likely – even if they come under the influence of more determined accountability policy and more intelligent, outcomes-driven subsidy policy – to remain largely as they are.

Why rely only and reflexively on installed colleges for reform?

Why not also invite into the sector a new breed of tightly monitored, clever college startups that can take a new run at college in search of break-through designs — free of the fixed costs, fixed mindsets, and fixed models of existing colleges?

The Postsecondary Commission is dedicated to this idea. We believe in a movement of new colleges that can uncover, refine and scale college designs that produce break-throughs in student outcomes and that agree, in exchange for access to public aid, to clear accountability and total transparency.

To enable this movement of new colleges, new models of accreditation will be needed — ones that, unlike the status quo described here, take a direct and expert interest in vetting, approving, scaling and monitoring new colleges.

In the blogs ahead, I’ll write more about the need for new colleges and new approaches to accreditation to enable them.

Until then, enjoy the summer.